Once upon a time

Traveling through time along the streets of Talloires

Among the string of charming villages scattered along the lake, Talloires, referred to as the pearl of Lake Annecy, figures among the two or three that attract the most visitors.

The perfect opportunity to embark on a voyage through time, listening to the hidden stories told on guided tours every Tuesday in July and August.

© Gilles Piel / Talloires, along the shores of Lake Annecy

An imperial favorite

In 1860, visiting the bay for the very first time proved a revelation for Empress Eugenia, who traveled to the area with her husband, Napolean III, to celebrate France’s annexation of the Savoie. She apparently exclaimed, “My God, it’s so beautiful.” The lavish festivities organized for the occasion included fireworks as the couple passed by the Talloires Bay on their lake cruise. The empress wrote about the memorable and “captivating” experience in her memoirs.

One year later, she offered the City of Annecy a gift, the “Couronne de Savoie,” a forty-meter long passenger steamboat. This Venetian celebration was the precursor to today’s “Fête du Lac” lake festival.

© Gilles Piel / The view of Talloires Bay from Lake Annecy

Tourism's beginnings

As early as the mid-19th century, with the rapid expansion of the railways, Talloires, in vogue at the time, started to attract artists, intellectuals, and political personalities due to its extremely classy and prestigious reputation. Mark Twain, the legendary American author who wrote such well-known works as Tom Sawyer, penned fondly in his “Travel Letters” about his stay at the abbey in 1891. André Theuriet, a member of the French Academy, lived in Talloires and bolstered its fine reputation as a tourist destination in 1890 in an article he wrote for Le Figaro. Gabriel Lippman, a French physicist and inventor of color photos took his very first photo in the cloister of the abbey in 1902. Even Winston Churchill and President Richard Nixon, as well as other illustrious personalities, visited Talloires.

© Françoise Cavazzana / Auberge du Père Bise Inn, an institution in Talloires

Painter Paul Cézanne immortalized the bay, and during a stay at the Abbaye in 1896 he painted, “Le Lac d’Annecy” (Lake Annecy), also known as “Le Lac bleu” (Blue Lake), now on display at the Courtauld Institute in London.

Paul Cezanne's painting, "Le Lac bleu"

At the time, few establishments had the ability to host and feed this type of high-society clientele. In 1903, to address the issue, Marie and François Bise, the latter know as “Le Père Bise”, founded the now famous inn that would stay in the family for four generations. Magali and Jean Sulpice took over in 2016, and remains a local institution to this day.

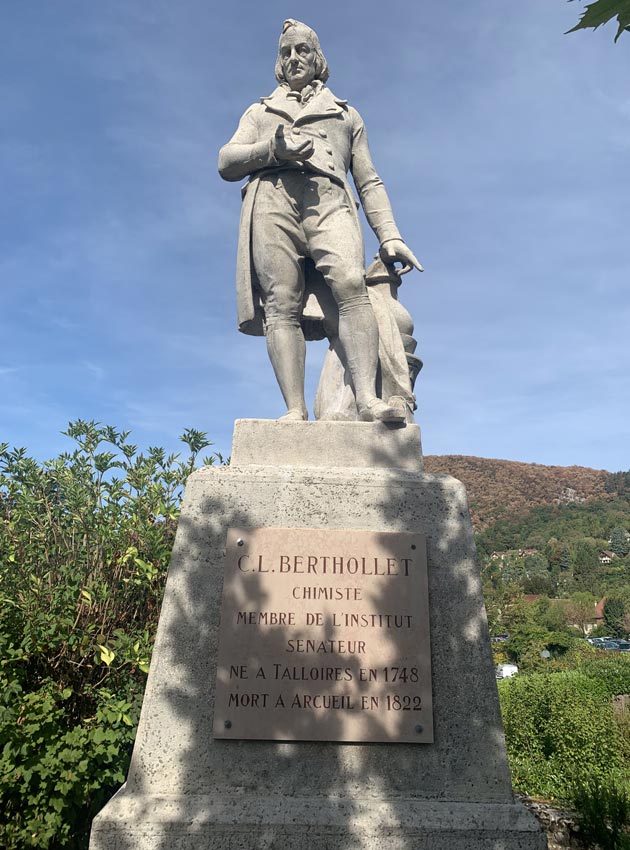

The statue of Claude-Louis Berthollet

Claude-Louis Berthollet’s statue presides over Astier Square, a small plaza next to the Tourism Office and facing the home where he was born and raised, currently the town’s City Hall. The statue stands next to a monument commemorating the partisans from Talloires who joined the Resistance during World War II. Claude Berthollet, born in 1748 at a time in history when the Savoie was still part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, became a chemist after his time as a brilliant university student in Annecy, Paris, and Turin. He studied with Antoine Lavoisier, one of the first professors to teach at France’s prestigious Ecole Polytechnique.

So, what exactly did he do to earn a statue in Talloires, another in Annecy’s Jardins de l’Europe Park, and a high school in his name? He discovered that chlorine fades colors, and developed a procedure to whiten canvas by using sodium hypochlorite; in other words he invented bleach!

© Aude Pollet Thiollier / Claude-Louis Berthollet, inventor of bleach

The Abbaye's tormented history

With help from Germain, the Priory was founded between 1018 and 1032 by monks from the Savigny Abbey and from Lyon. It became a Royal Abbey in 1674. The monks, living the good life there, apparently veered off the righteous path and into depravity, which sparked a minor revolt among the local population. François de Sales tried to intervene but failed, apparently chased away by gun fire.

The monastery was damaged several times, including by fires in 1520 and 1670, before being rebuilt. When revolutionaries arrived in Talloires in 1792, determined to erase all traces of the Old Regime, they placed the final nail in the coffin by burning the archives to the ground. It is said that the bells from the abbey’s old church lie at the bottom of the lake! While the truth of the story still requires conclusive evidence, it successfully romanticizes the past of this truly amazing place.

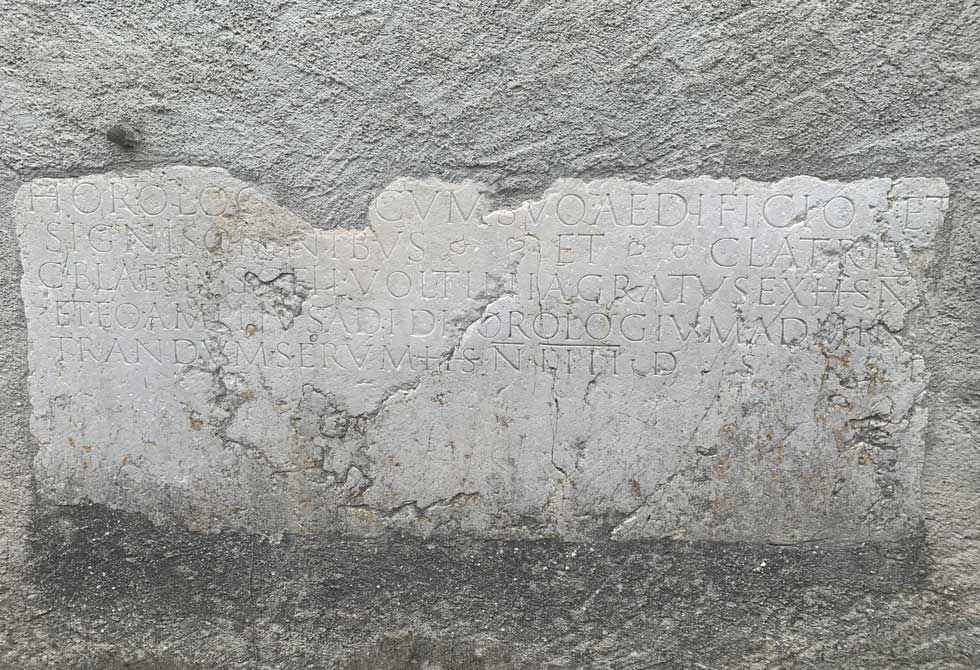

© Marie-Paule Rouge-Pullon / The Roman inscription near the priory in Talloires

As we continue along the path that leads to the priory that currently houses the European headquarters for Boston’s Tufts University, which hosts students during the summer season, you can read the Roman inscription dating from the era when Annecy was a small Gallo-Roman village named Boutae. The inscription reads, “Caius Blasius from the Voltinia tribe, donated a clock and the building that houses it, as well as the slave in charge of its use for the sum of 40,000 sesterces” (approximately €30,000 today).

Saint Germain Church in Talloires

Germain de Montfort was a Benedictine monk at Savigny Abbey. In 1018, he was sent to Talloires by Ermengarde, after her husband Rudolph III, King of Burgundy, relinquished the area, to build a priory. Geramin became the first prior in Talloires.

After construction finished, he decided to move to cave in a cliff above Talloires to live as a hermit, dedicating his life from, 1033 to 1060, to prayer, solitude, and penitence, influenced by trip to the holy land during which the hermits living in the desert made an impact. His fellow monks built him an oratory to celebrate mass. Legend explains that angels carried him every day back and forth from the priory in Talloires. He died at 96 years old and was buried in the cave.

© C. Max / Following in the footsteps of Saint Germain

The story does not end here. In 1621, Saint Francis de Sales, Bishop of Geneva living in Annecy, wanted to restore Saint Germain’s level of devotion, so ordered the oratory to be restored. Over the years, a series of improvements transformed the oratory into a chapel, which was then, in the second half of the 19th century, rebuilt in neo-gothic style, while preserving the Baroque altar. The Saint-Germain-sur-Talloires parish was created in 1836 and the chapel consecrated as a church by Bishop Pierre-Joseph Rey, even though it had no bell tower or sacristy. Today, it provides a peaceful oasis to reflect and meditate, with breathtaking views of the lake.

Visit the church as part of a pleasant hike that starts in Talloires, one that offers amazing views of the lake and mountains as well as the opportunity to explore the upper part of the village. Download the hike onto your smartphone using the ViAnnecy app. It takes approximately 2.5 hours to complete the loop.

© C. Max / The view of Lake Annecy from above Saint Germain

*Just for fun, here are a few excerpts from the Mark Twain’s “Travel Letters” written in 1891 and 1892.

“…Then at the end of an hour you come to Annecy and rattle through its old crooked lanes, built solidly up with curious old houses that are a dream of the middle ages, and presently you come to the main object of your trip–Lake Annecy. It is a revelation, It is a miracle. It brings the tears to a body’s eyes it is so enchanting. That is to say, it affects you just as all things that you instantly recognize as perfect affect you–perfect music, perfect eloquence, perfect art, perfect joy, perfect grief. It stretches itself out there in the caressing sunlight, and away towards its border of majestic mountains, a crisped and radiant plain of water of the divinest blue that can be imagined. All the blues are there, from the faintest shoal water suggestion of the color, detectable only in the shadow of some overhanging object, all the way through, a little blue and a little bluer still, and again a shade bluer till you strike, the deep, rich Mediterranean splendor which breaks the heart in your bosom, it is so beautiful.

And the mountains, as you skim along on the steamboat, how stately their forms, how noble their proportions, how green their velvet slopes, how soft the mottlings of sun and shadow that play about the rocky ramparts that crown them, how opaline the vast upheavals of snow banked against the sky in the remotenesses beyond–Mont Blanc and the others–how shall anybody describe? Why, not even the painter can quite do it, and the most the pen can do is to suggest.

Up the lake there is an old abbey–Talloires–relic of the middle ages. We stopped there; stepped from the sparkling water and the rush and boom and fret and fever of the nineteenth century into the solemnity and the silence and the soft gloom and the brooding mystery of a remote antiquity. The stone step at the water’s edge had the traces of a worn-out inscription on it; the wide flight of stone steps that led up to the front door was polished smooth by the passing feet of forgotten centuries, and there was not an unbroken stone among them all. Within the pile was the old square cloister with covered arcade all around it where the monks of the ancient tunes used to sit and meditate, and now and then welcome to their hospitalities the wandering knight with his tin breeches on, and in the middle of the square court (open to the sky) was a stone well curb, cracked and stick with age and use, and all about it were weeds, and among the weeds moldy brickbats that the Crusaders used to throw at each other. A passage at the further side of the cloister led to another weedy and roofless little enclosure beyond, where there was a ruined wall clothed to the top with masses of ivy and flanking it was a battered and picturesque arch. All over the building there were comfortable rooms and comfortable beds, and clean plank floors with no carpets on them. In one bedroom upstairs were half a dozen portraits, dimming relics of the vanished centuries–portraits of abbots who used to be as grand as princes in their old day, and very rich and much worshiped and very holy; and in the next room there was a howling chromo and an electric bell. Down stairs there was an ancient wood carving with a Latin word commanding silence, and there was a spang new piano close by. Two elderly French women, with the kindest and honestest and sincerest faces, have the abbey now, and they board and lodge people who are tired of the roar of cities and want to be where the dead silence and serenity and peace of this old nest will heal their blistered spirits and patch up their ragged minds. They fed us well, they slept us well, and I wish I could have staid there a few years and got a solid rest.”

Copyright:

- © Françoise Cavazzana

Journalist: Aude Pollet Thiollier

Translation: Darin Reisman